Blame the tech, not the users

Daniel Tkacik

May 17, 2019

When a personal device has fallen victim to some sort of cyberattack, users often misdiagnose what exactly is going on. But they’re not the ones to blame. Those are the conclusions of a recent study led by researchers in Carnegie Mellon University’s CyLab.

Source: Carnegie Mellon University's College of Engineering

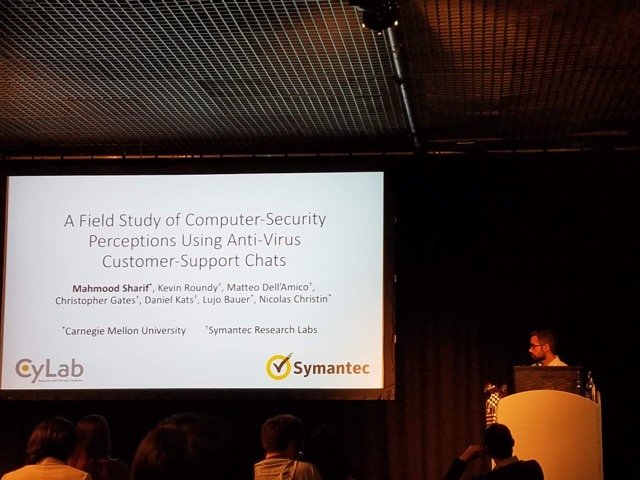

CyLab researcher and Electrical and Computer Engineering Ph.D. student Mahmood Sharif presents the findings of his study at the ACM CHI conference in Glasgow.

“I can’t assign a bad letter grade to the user, because it’s not their fault,” says Mahmood Sharif, a Ph.D. student in the department of Electrical and Computer Engineering (ECE). “Instead, we should improve technology to better protect users.”

In a study presented last week at the 2019 ACM CHI conference in Glasgow, Sharif and his colleagues wanted to understand how accurately people perceived security issues with their computers. Understanding this perception gap would help inform ways to improve the technology itself.

“These findings enable us to make recommendations on how to improve user security,” Sharif says.

To gain an understanding of how users perceived security-related issues, the researchers combed through thousands of problem descriptions of suspected computer security problems that users submitted to the customer-support desk of a large anti-virus vendor from 2015 to 2018. The researchers then compared what the users were conveying—symptoms they were describing, what they thought was the issue, and what they believed to be the root cause—with expert diagnoses, provided by the researchers, of the actual issues.

It turned out that experts and users agreed on a lot, with an exception for when users suspected successful intrusions (i.e., malware infections and unauthorized remote accesses).

“When users suspected successful intrusions, experts agreed less than half the time,” says Sharif. “Many of the misdiagnosed intrusions were scams or resulted from confusing warnings displayed to the user.”

These findings enable us to make recommendations on how to improve user security.

Mahmood Sharif, Ph.D. Student, Electrical and Computer Engineering

Surprisingly, the researchers found that users’ and experts’ diagnoses matched 70 percent more when users expressed doubt – using phrases like, “I think” or “I believe” or explicitly asked for help in diagnosing the issue – than when they felt certain about their diagnoses.

“This tells us that customer-support agents need to be wary of users’ diagnoses, particularly when they sound certain,” Sharif says.

With an understanding of these trends, the researchers suggest that it may be possible to automatically extract symptoms and predict expert issues. This may help improve the customer-support experience, for example, by assigning particular cases to particular agents that are specifically trained to give support in those areas.

The other researchers who authored the study included Symantec researchers Kevin Roundy, Matteo Dell’Amico, Christopher Gates, and Daniel Kats, ECE and Institute for Software Research (ISR) professor Lujo Bauer, and ISR and Engineering and Public Policy professor Nicolas Christin.